In the history of Iran, we repeatedly encounter events that are connected with the history of Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam. To understand these events correctly, it is necessary to have a general familiarity with the history of these lands. Without such knowledge, many occurrences in Iranian history remain unclear.

Nevertheless, an extensive treatment of the history of Babylonia and other countries lies outside the main subject of this writing.

The Sumerians and the Akkadians

The Sumerians and the Akkadians lived in southern Mesopotamia, a land that later, in the first millennium BCE, came to be called “Chaldea.” It is not possible to determine with certainty the exact boundaries of the realms of Sumer and Akkad; it is only known that Uruk, Nippur, Sippar, Kish, and Babylon were among the important cities of Sumer and Akkad. The Sumerians and the Akkadians were two different linguistic and ethnic groups that, over time, became intermixed.

Note: Kish was located in southern Mesopotamia, in present-day Iraq, near Babylon, and is distinct from the modern island of Kish.

Note: The name Chaldea was given to Babylon by the Assyrians because of the presence of the Chaldeans, who were of Semitic origin, in that city. This name appears in Assyrian inscriptions from the ninth century BCE.

Since the history of Sumer and Akkad goes back several thousand years before the Common Era, their history cannot be called the history of Chaldea. Therefore, the histories of Sumer and Akkad must be examined separately. Among scholars, there has been disagreement as to which of these peoples took possession of this land earlier. Although this question has not yet been conclusively resolved, today most scholars believe that before the arrival of the Semitic peoples, the Sumerians lived along the shores of the Persian Gulf.

Note: The script used by the Sumerians was cuneiform. Archaeological evidence indicates that this writing system most likely emerged within Sumerian civilization itself. The oldest known tablets originate from this land. For this reason, the Sumerians are the earliest people who are documented to have used writing to record their language.

The Sumerians were most likely a people who emerged in southern Mesopotamia itself and gradually developed an urban civilization. Archaeological evidence shows no sign of a sudden migration from the north or east. In the cultural layers of southern Mesopotamia, there is no clear break that would indicate the arrival of a new population. The Sumerian language has no known linguistic relatives; it is neither Semitic nor Indo-European. The absence of linguistic kinship may—though not conclusively—be an indication of its antiquity. Cities such as Uruk and Lagash were formed from the outset in the same region, and in their architecture and rituals, there is no sign of imported concepts.

Note: A ziggurat was a tall, stepped structure built in the major cities of Mesopotamia. It had a religious function and was considered the place of worship of each city’s god. A ziggurat was neither a tomb nor a gathering place for ordinary people; it was regarded as a sacred platform for the presence of the gods. People believed that the higher the place of worship, the closer it was to the sky. For this reason, ziggurats were built in ascending layers. Each level was placed upon another, and a narrow path led to the highest part. The main materials were mudbrick and baked brick. The walls were sometimes decorated with paint or tiles to enhance the building’s splendor. These structures could be seen from afar and were a sign of a city’s power. A ziggurat was usually located at the heart of the city, alongside palaces, storehouses, and administrative buildings. In this way, religion, politics, and the economy were brought together in a single center, around which urban life took shape.

Note: The author believes that the idea of closeness to the sky was more a pretext than a real reason, intended to make the religious structure more magnificent. The primary aim was to instill a sense of awe and grandeur in a religious idea and to exert greater influence over its followers. This approach was not limited to ziggurats; the same pattern can be seen in the pyramids of Egypt, Greek temples, Gothic churches, and large Islamic mosques.

On the other hand, the Akkadians were a Semitic-speaking people who most likely gradually moved southward from the Semitic-speaking regions of northern or western Mesopotamia. The Akkadian language belongs to the East Semitic branch and is related to the Semitic languages of the Levant and northern Arabia, which are mostly West Semitic. From about three thousand years BCE onward, Semitic names gradually appear in Sumerian documents. This suggests peaceful coexistence rather than a sudden invasion. The Akkadians adopted the Sumerian cultural framework while also transforming it—a framework that included cuneiform writing, the administrative system, and the pantheon of gods. This process indicates gradual population influence rather than the replacement of one people by another.

Sumerian Religion

In Sumerian belief, each city had its own particular god. The inhabitants of each city regarded their own god as superior to those of other cities. Nevertheless, three gods were recognized and worshiped in most cities. Anu was the god of the sky. Enki was considered the god of the depths and hidden waters. Enlil was regarded as the god of air, wind, and royal authority. The Sumerians also believed in invisible forces. They feared evil spirits, demons, and Jinn, believing that these forces could harm human life. To protect themselves, they made sacrifices and offered vows and gifts.

Note: In Sumerian civilization, we encounter for the first time a written system of thought concerning invisible forces. The Sumerians gave names to these forces and assigned a role to each. These beliefs were recorded in religious and ritual texts. Here we encounter concepts very close to what we today call spirit, demon, or Jinn. These beings could cause illness, bring misfortune, or disturb human peace. To ward them off, rituals, prayers, and sacrifices were performed. In this respect, Sumer represents the starting point for the historical documentation of such beliefs.

Note: It appears that the concepts of spirit and jinn, which had their roots in the ancient traditions of Mesopotamia, gradually spread through cultural and historical exchanges. These concepts later entered the intellectual world of Abrahamic religions such as Judaism and Islam. These religions arose within the same cultural sphere and reworked and re-created these ideas within a new framework.

The Sumerians fashioned gods in the form of statues. These statues were not the god itself, but the place of its presence. If a statue of a god was taken from one city to another, people believed that the god of that city had been captured. For this reason, they considered the city’s independence and power to be lost. In Babylonian narratives, it is said that some gods had spouses and others were the children of gods. Sumerian gods were imagined as very similar to humans: they became angry, showed affection, felt jealousy, and at times acted cruelly.

Note: The idea of gods as human-like beings and the attribution of human emotions and relationships to invisible forces were first clearly recorded in Mesopotamia, including Sumer. This pattern later reached the lands around the Aegean Sea through cultural contact. Nevertheless, the Greek gods are not copies of Sumerian gods, but a separate re-creation of a shared intellectual heritage.

Photo by Nic McPhee from Morris, Minnesota, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia

Sumerians built temples mostly from mudbrick. The place of worship was located at the highest part of the structure, and priests wielded great influence in the city. They said that the gods, like kings, lived in luxury and abundance. For this reason, temples were filled with treasures, grain, food, and various goods. These places were not only sites of worship but also the economic centers of the city. A large portion of trade was conducted through the temples, as if the gods themselves were owners and merchants.

Note. In Mesopotamian civilizations, especially Sumer, Akkad, and Babylon, we encounter for the first time the clear idea that the ruler derives his power from the gods. The king is either chosen by the god, represents the god, or has come to power by divine will. This outlook later continued in other lands as well. In medieval Europe, the Church granted legitimacy to kings, and in Iran, the Safavids and Qajars called the shah the “shadow of God.” In late-twentieth-century Iran as well, the Islamic jurisprudence (Faqih), through the Hidden Imam (Al-Mahdi), becomes the executor and representative of divine will on earth.

Note. In very ancient times, humans regarded the forces that affected their lives as “sacred.” This was a way of understanding the world, calming fear and insecurity, creating social order, and legitimizing power and law. With this perspective, the world acquired meaning, and life became more bearable. Over time, polytheism gradually gave way to belief in a single god. This transformation was not sudden but proceeded step by step. First, one god became superior among the gods. Then the worship of one god became prevalent, while the existence of other gods was still accepted. Finally, belief in a single god took shape, and the other gods were set aside. The idea of one god emerged from within these polytheistic systems. Powers that had previously been distributed among various gods were gradually concentrated in a single divine being. Monotheism was the result of this concentration. The earliest signs of this tendency go back several thousand years. In Egypt (around 3,400 years ago), the religious reform of Akhenaten is an example of the elevation of one god. In the land of Israel as well (around 3,000 years ago), the worship of Yahweh began—a belief in one god, though not yet in the sense of complete monotheism. Full monotheism developed later, especially after the Babylonian Exile.

The Ensi of Sumer

In the earliest periods, the head of the city was called the Ensi. People believed that he ruled by the will of the city’s god and was the god’s representative on earth. The Ensi administered city affairs in accordance with the wishes of the gods. Thus, they were a kind of minor kings who held religious, civil, and military authority.

Among the rulers of the Sumerian city-states, some came into conflict with the land of Elam. One of the most famous was Eanatum, the Ensi of the city of Lagash, who lived in the mid–third millennium BCE. The surviving inscriptions show that he took part in battles with the Elamites and spoke of victory in his own writings.

Nevertheless, the historical evidence does not present a simple picture. The people of Elam, especially those living in the mountainous regions, repeatedly raided Sumerian cities. These conflicts were largely reciprocal and did not proceed in a single direction. The ensis of Lagash sometimes managed to repel these attacks, but one cannot speak of a complete and lasting defeat of Elam.

In later periods as well, clashes between Lagash and Elam continued. The importance of these events lies less in the battles themselves than in the texts that refer to them. Some of these writings are among the oldest examples of the recording of political thought and events in the Sumerian language. They show that writing gradually went beyond recording economic matters and came to be used to narrate historical events.

The Akkadians and Semitic Rulers

In southern Mesopotamia, the civilizations of Sumer and Akkad were present at the same time and developed alongside one another. The Sumerians mostly lived in the ancient cities of the south, while the Akkadians, whose language was Semitic, gradually gained political power in the same space. What occurred was not the end of Sumer, but the political dominance of Akkad over many Sumerian cities.

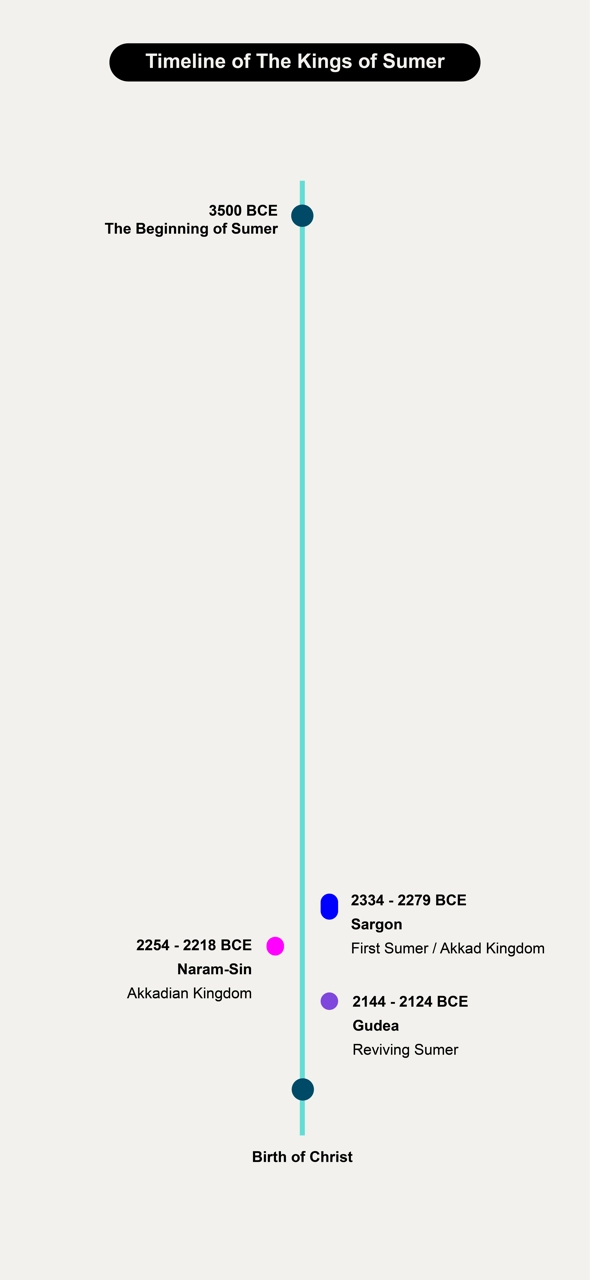

The turning point in this process came with the rise of Sargon. In the twenty-fourth century BCE, he was able to bring various Mesopotamian cities under his rule and create the first empire-like political structure in human history in this region. His realm extended westward to the Levant area and eastward to the foothills of the Zagros mountain range. This expansion did not always mean direct and stable control, but it did demonstrate Akkadian political and military influence. It is thought that the city of Akkad became the capital of the Akkadian state at the same time that Sargon came to power.

Dark green indicates the core territory; light green indicates the sphere of military influence.

During the time of Sargon and his successors, the Akkadian language—a Semitic language—gradually gained official status. Many Sumerian texts, especially religious, ritual, and legal writings, were translated into Akkadian. This ensured that the intellectual heritage of Sumer did not disappear and could still be read and understood in later periods. Centuries later, during the reign of Ashurbanipal, numerous copies of these texts were collected and recopied in the library of Nineveh, which is why they have survived to this day.

Relations between Akkad and Elam were tense. Military campaigns and Akkadian raids into Elamite regions are reflected in the sources, but it is not clear that Elam ever became fully integrated into the Akkadian realm. It is thought that in certain periods, Elam was under Akkadian military pressure and may have been forced to pay tribute, but this situation was neither stable nor permanent.

After Sargon, rulers such as Naram-Sin continued the path of conquest. Naram-Sin carried out campaigns in the mountainous regions of the Zagros, including the land of the Lullubi, in what is now Kermanshah Province. His famous rock relief in this region depicts the Akkadian king’s victory over the Lullubi enemies and is considered one of the most important artistic and political monuments of that period.

Photo by Rama, CC BY-SA 3.0 fr, Wikimedia

After the decline of Akkadian power, a period of instability began. A group known as the Gutians entered Mesopotamia from the mountainous regions of the Zagros. Little precise information is available about their linguistic and ethnic origins. The Gutians dominated parts of Mesopotamia, including the regions of Babylon, for a time. This period was marked by political instability, and older powers, including Elam, were also drawn into this turmoil.

Thus, the history of Akkad is not a simple replacement after Sumer, but part of a complex process of coexistence, competition, and shifting power in ancient Mesopotamia.

The Revival of Sumer

In the late third millennium BCE, after the collapse of the Akkadian Empire, the city of Lagash once again became one of the major centers of power in southern Mesopotamia. During this period, Gudea, the ensi of Lagash, ruled and focused above all on organizing affairs, stabilizing religious order, and constructing temples and public buildings.

The inscriptions of Gudea show that materials such as stone and wood for these construction projects were obtained from lands such as the Levant, Arabia, and Elam. This extensive trade network reflects the economic and cultural influence of Lagash in the region. From a military perspective, it appears that Elam, in general, and Anshan in particular, were influenced by the rule of Lagash during this period, but it cannot be stated with certainty that these regions were conquered by Lagash.

Photo by Metropolitan Museum of ArtCC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0), Wikimedia

Soon afterward, at the beginning of the twenty-first century BCE, political power shifted to the city of Ur, and the Third Dynasty of Ur was established under Ur-Nammu and his successors. In this period, the Sumerian language once again became the official and administrative language, although Akkadian remained alive in everyday speech. This change reflects a revival of Sumerian cultural traditions within the framework of a centralized state.

During the reign of Shulgi, the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, the administrative and military structure of the state was strengthened, and campaigns were conducted against neighboring lands, including Elam. Nevertheless, control over these regions was unstable, and the state of Ur III was repeatedly forced to send troops to suppress revolts. Elam was never fully and permanently integrated into the Sumerian realm, and ultimately, these struggles contributed to the weakening and fall of the state of Ur.

The Extinction of the Sumerian State

The fall of the Sumerian state, especially the Neo-Sumerian state of Ur III, was not sudden. This collapse occurred at the end of the third millennium BCE as a result of the accumulation of internal and external pressures. The central government of Ur III faced repeated revolts in Elam, pressure from Amorite tribes, and economic and administrative disorder. These pressures gradually eroded the state’s strength.

The Amorites were Semitic peoples who mostly lived as nomads or semi-nomads. Their main habitat was in western Mesopotamia and the regions of the Levant. The slow but steady infiltration of these groups made it increasingly difficult for the state of Ur III to maintain control over cities and trade routes.

Around 2004 BCE, Elamite forces under the leadership of Kudur-Nahhunte attacked the city of Ur. The city was plundered, and Ibbi-Sin, the last king of Ur III, was taken captive. This event is considered the symbolic end of the state of Ur III, although Elam was unable to establish lasting rule over all of Sumer.

After the fall of Ur, a power vacuum emerged in southern Mesopotamia. During this period, local kingdoms such as Isin and Larsa arose, mostly under Amorite rulers. The Sumerians disappeared as an independent political power, but Sumerian culture, religion, and language remained alive for centuries and influenced later Mesopotamian civilizations.

The Contributions of the Sumerians

The Sumerians are among the earliest peoples who are documented as having achieved urban life, political organization, and a structured economy in southern Mesopotamia. One of the earliest centers of civilization in human history emerged in this land, and many innovations spread from this region to other parts of the world.

One of the most important achievements of the Sumerians was the emergence of the earliest known writing system, cuneiform. This script was initially used for administrative and economic purposes and gradually became a tool for recording religious, ritual, and legal ideas. The emergence of writing played a major role in the expansion of social organization and the transmission of knowledge in the ancient world.

The Sumerians were also among the first peoples to record written laws and a legal order. This legal tradition continued in later periods and influenced the law codes of subsequent civilizations, including the laws of Hammurabi. In addition, the earliest recorded examples of mathematics, the sexagesimal number system, calendars, astronomical observations, and ritual–empirical medical practices appear in Sumerian texts.

Archaeological findings indicate that part of the knowledge of later civilizations reached the Greek world through intermediary traditions such as Akkadian and Babylonian. Nevertheless, the Greeks were independent re-creators of this heritage, not direct heirs of Sumer.

Excavations, especially in the city of Ur, show that before the formation of Sumerian civilization, older cultures existed in this region. Sumerian influence is seen less as a direct expansion of civilization and more in the form of networks of trade and cultural exchange throughout ancient Western Asia.

Sources:

Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians

Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

Mario Liverani, The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy

Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East

The Cambridge Ancient History, Vol. III

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Mesopotamia”; “Kish (ancient city)”

Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Chaldea”

Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians

Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods

Denise Schmandt-Besserat, How Writing Came About

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sumerian language”; “Cuneiform writing”

Ignace J. Gelb, A Study of Writing

I. M. Diakonoff, Semito-Hamitic Languages

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Akkadian language”

Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Akkadian Language”

Andrew George, Babylonian Topographical Texts

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sumerian religion”

Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Mesopotamian Religion”

D. T. Potts, The Archaeology of Elam

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Sumer”; “Akkadian Empire”; “Ziggurat”

Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Lullubi”

Encyclopaedia Iranica, “Lullubi”