Before Iran - Assyria

Note: I write these lines at a time when, recently, thousands of my dear compatriots in Iran lost their precious lives in the protests of 8–9 January 2026. This event had a profound and heartrending effect on me and encouraged me, more than ever, to continue the struggle against ignorance in my beloved country, Iran. May my writing be a tribute to the pure blood of the martyrs of the homeland.

The Assyrians were a Semitic people and belonged to a branch of the Semitic-speaking peoples of Mesopotamia. From the beginning, they were present in the northern parts of this land and had close cultural and political ties with Babylonia. In later periods, the center of their life shifted toward the middle course of the Tigris River and the surrounding mountains, where a state known as Assyria took shape.

The name of this land was derived from its principal deity, Ashur. The Assyrians also recognized and worshipped the Babylonian gods, but they regarded Ashur as superior to the other gods. In their belief, as the power of the Assyrian state increased, the splendor of this god grew, and the gods of other cities assumed a lower rank. The capital of Assyria was initially Assur, but in later periods, Nineveh was chosen as the political center.

Note: The author believes that one of the important functions of religion in societies, including in the land of Assyria, was to legitimize the political and military power of rulers. Religion was not limited to rituals and beliefs; rather, it served as an instrument for justifying and consolidating rulership. The Assyrian kings regarded themselves as representatives of the will of the god Ashur and explained political decisions and military campaigns within the framework of his desire. In this way, the king’s power appeared not as a human choice but as a divine matter, and obedience to him acquired a religious meaning. This pattern has been repeated throughout history. In contemporary Iran, the same pattern is also being employed by the rulers.

Note: In English-language sources, in order to avoid ambiguity, the names are written differently. The Assyrian state is referred to as Assyria, the Assyrian god as Ashur, and the Assyrian city as Assur. This method of naming helps the reader determine which concept the word “Ashur” denotes in each case and prevents confusion among the state, the god, and the city.

Note: Most scholars believe that the name of the country “Syria” is derived from Assyria. In ancient Greek sources, particularly in Herodotus’s writings, the term Syria was commonly regarded as a shortened form of Assyria. This name was used for the lands west of the Euphrates River. Today, this view is widely regarded as the dominant view in historical linguistics.

The name Assur first appears in historical sources during the time of Hammurabi, king of Babylon, and from this, it may be inferred that Assur was under Babylonian influence at that time. The exact time of Assur’s independence is uncertain, but the process generally took shape between the eighteenth and fifteenth centuries B.C.

The Assyrians were an agricultural people. They lived in a land where arable fields were fewer than those of the plains of Babylon and where the soil was less fertile. Therefore, the Assyrians decided to base their livelihood on benefiting from the labor of others. For this reason, they launched raids against neighboring lands at the beginning of spring each year. Their aim was either to turn a country into a tributary or to plunder rebellious cities. They killed as many people as they deemed necessary, took the rest captive, and carried them off to their own land. They forced the captives to perform hard labor, while they themselves lived in ease and luxury.

Naturally, the Assyrian state was formed on the basis of such an approach and, in terms of organization and structure, bore no resemblance to the Babylonian state. In Sumer and Babylon, each city had an independent ruler who usually bore the title of king and also possessed both religious and political authority. In these lands, the state was more the product of coexistence and consensus among these urban centers of power and had a feudal structure in which temples and the clergy played a decisive role.

By contrast, the Assyrian state was, from the outset, founded on a society of free farmers. These farmers constituted the main pillar of the Assyrian army, and warfare and raiding were regarded as part of their social life. For this reason, the Assyrian state was not a collection of semi-independent cities but a cohesive, militarily oriented structure that differed fundamentally from the Sumerian–Babylonian model.

For this reason, it is not surprising that Assyria became a warlike state and that its army gained renown among the contemporary forces of its time. One of the most frequently repeated characteristics in sources about the Assyrians is their extreme violence and ruthlessness toward the defeated. This behavior can be explained from two perspectives. First, in Assyrian official writings and inscriptions, violence was portrayed as an act to please the gods. In these texts, kings regarded their violent deeds as a sign of loyalty to the gods. Second, the Assyrians had a relatively small population, while the territories subject to them were extremely extensive. To prevent rebellion and secession in these lands, they employed a policy of instilling fear and rendering the conquered peoples powerless.

One of the clearest manifestations of Assyrian violence was the policy of intimidation and collective punishment. The large-scale deportation of populations and the complete destruction of rebellious cities were considered inseparable parts of this policy. Assyrian kings deliberately used overt violence to instill fear in their enemies and prevent the recurrence of rebellion.

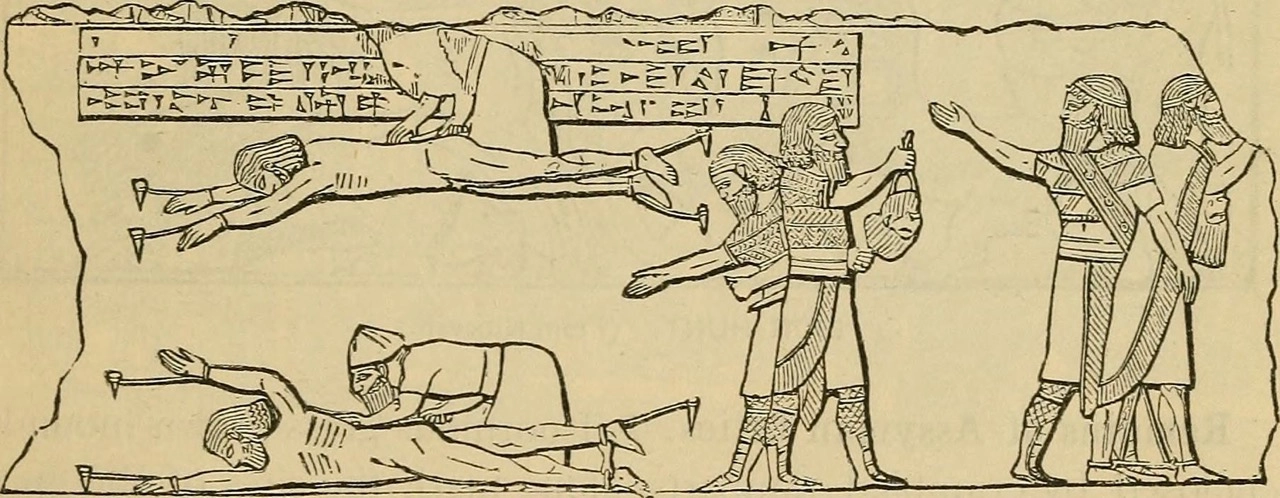

In royal inscriptions, this violence is described in detail. Scenes of severing limbs, blinding, hanging, and the display of the bodies of rebels are depicted. These descriptions were not intended for exaggeration or sensationalism, but rather demonstrated an official Assyrian policy of deterrence—a calculated and purposeful policy, not scattered or accidental violence.

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images

Note: In the author’s view, the use of overt violence to create fear and deterrence among rebels is a pattern that has been repeated many times in the history of Iran. The mass slaughter of cities such as Nishapur at the hands of Genghis Khan, or the erection of minarets and heaps of severed heads by order of Timur in the medieval period of Iran, and, in contemporary history, the large-scale and public executions of political opponents in the 1980s by order of Khomeini, are clear examples of this trend.

During the period of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the forced deportation of large populations from conquered lands to other parts of the empire became widespread. These relocations were often accompanied by coercion and violence and, in many cases, shattered the social and economic structures of the defeated regions.

In response to rebellions, the Assyrians at times resorted to the complete destruction of cities. A clear example of this approach is Ashurbanipal’s campaigns against Elam. Historical sources speak of the destruction of cities, the demolition of temples, and widespread slaughter. The aim of these actions was not merely the suppression of a rebellion, but the elimination of any possibility of the enemy’s reconstruction of power in the future.

The Assyrian state endured for nearly a thousand years and expanded its borders in all directions. From the west, it eliminated the remnants of the Neo-Hittite states in Anatolia and northern Syria, then subjugated Phoenicia and Palestine, and advanced to the borders of Egypt. From the east and southeast, it extended its influence into parts of the Iranian Plateau and, for a time, forced Media and Persia to tributary status. Elam, too, suffered severe damage in the Assyrian campaigns and was greatly weakened.

Note: Here, Persia refers to the region of Persis (Parsa) in southwestern Iran, not to the Persian Empire that later formed. This region was inhabited by the Persians, an Iranian-speaking people who belonged to the Indo-Iranian—more specifically, Aryan—cultural and linguistic tradition. They had settled on the Iranian Plateau well before the Assyrian period.

Finally, the Assyrian state was brought to an end by the Medes. The Assyrian language was similar to the Babylonian language, but in later periods, Aramaic also became widespread in this land. The Assyrian script was regarded as the same Babylonian cuneiform script. Numerous inscriptions and writings from the kings of Assyria remain, as they were interested in recording events and reporting their victories. The Assyrians made clay tablets, wrote on them, baked them in a fire, and preserved them. In this way, the writings became durable, and collections came into being that may be called libraries.

Many of these tablets were buried in the soil at the time of Nineveh's destruction and have now been recovered through archaeological excavations. These tablets are considered among the most important sources for understanding the history of ancient periods. Thousands of them are kept in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Among these works, the famous library of Ashurbanipal, discovered at Kuyunjik—near present-day Mosul—holds a special place.

The Assyrians also left behind many works in the field of crafts. The kings of Assyria recognized two principal duties for themselves: first, war, and second, the construction of new cities, carried out through the hard labor of captives. For this reason, architecture, stone carving, engraving, and the making of stone reliefs in Assyria made remarkable progress. Some of these reliefs, especially scenes of royal hunts or official ceremonies, are fashioned so naturally—particularly in the depiction of the movement of animals such as horses and gazelles—that they still astonish the viewer today.

Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia

In other crafts as well—such as goldsmithing, khatam inlay work, and tile-making—the Assyrians also possessed skill. The Phoenicians, inspired by these works, produced many objects and spread them throughout the ancient world. Later, these same models were imitated in European lands and provided the groundwork for the growth of industry in those regions.

Historical Periods of Assyria

The history of Assyria is divided into three periods:

Old

Middle

Neo

Old Assyria

Old Assyria gradually took shape in a period roughly from 2000 to 1400 B.C. At this time, Assyria was not yet a warlike empire. Rather, we are faced primarily with a city-state whose identity was founded upon commerce. The strength of Assyria in this period was derived more than anything else from extensive trade with distant lands, not from military campaigns and warfare.

The clearest indication of this period is the activity of Assyrian merchants in central Anatolia—present-day Turkey. In this region, they established commercial centers known as Karum. The best-known example is the Karum of Kanesh at Kültepe, in modern Turkey. Thousands of clay tablets recovered from these centers show that the Assyrians played a fundamental role in the trade of goods such as tin, textiles, and silver. These documents also testify to the use of contracts, loans, commercial partnerships, and advanced legal regulations.

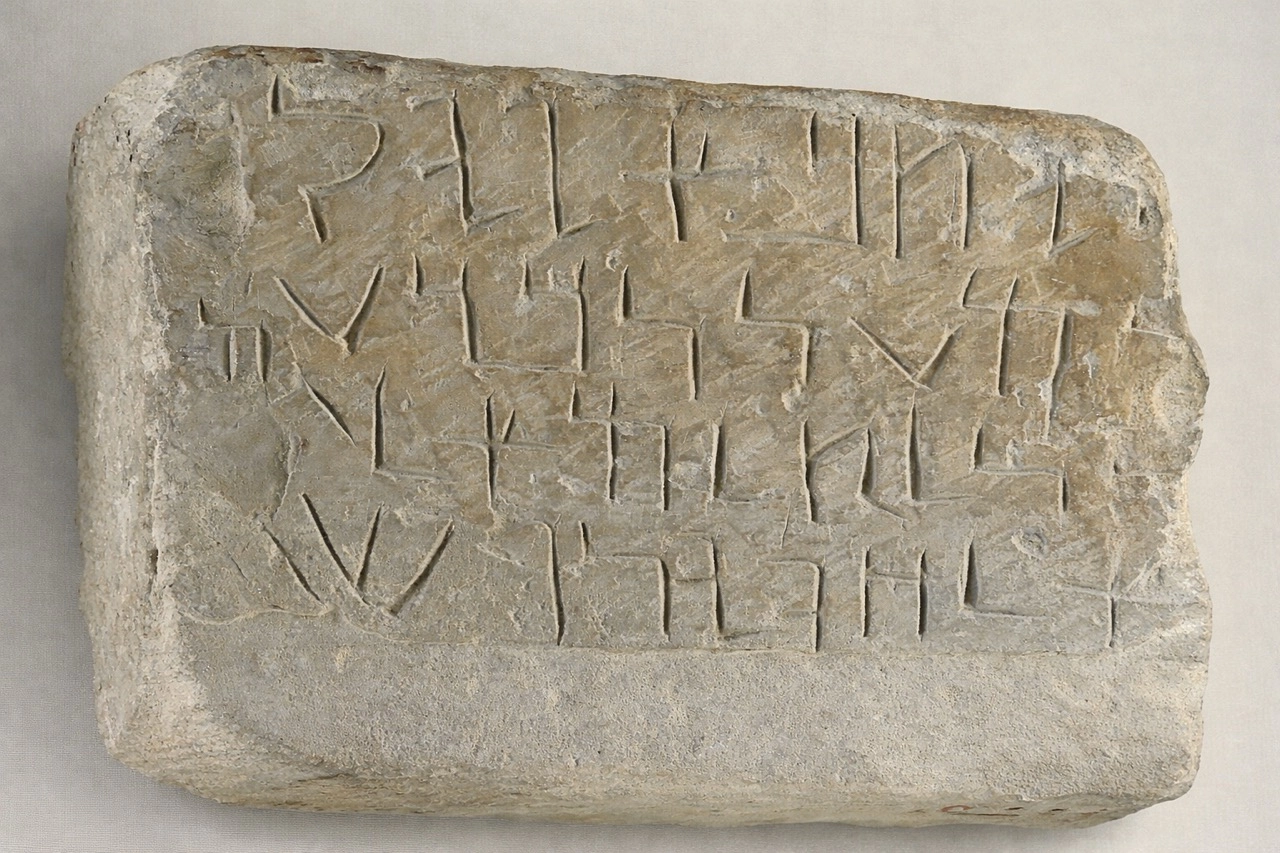

Note: This image shows a sample of Old Assyrian correspondence tablets. The letter was written on the central tablet and sometimes placed inside this clay packet for protection, confidentiality, or legal authentication. The clay packet was sealed with cylinder seals. Each party to the contract impressed its own distinctive designs and symbols by rolling the cylinder over the soft clay, so that identity and consent were recorded. These seals served as signatures, indicating that the text inside the clay packet was accepted by both parties. If a dispute arose between the parties to the contract, the clay packet would be broken in the presence of others, such as an arbitrator or a judge. After the covering was broken, the tablet's text would be read, and the contract's contents would become clear. This practice served both to resolve disputes and to demonstrate the document’s legal validity. At the same time, this method also helped preserve the confidentiality of private letters, such as the image above. As long as the sealed clay packet remained intact, no one had access to the text inside the tablet, and the writing remained protected. In this way, both the security of the text and trust between the parties were ensured.

From a political perspective, Old Assyria did not yet possess a unified, conquering military force. The king of Assur, rather than being a war commander, fulfilled primarily religious and judicial roles. His power depended on urban institutions and the merchant class. Assyrian society at this time had an urban and economic structure and had not yet reached the model of a centralized and military state characteristic of later periods.

Overall, Old Assyria can be regarded as the economic and institutional foundation of Assyrian civilization. During this period, the legal, administrative, and financial foundations were established. It was precisely these infrastructures that later provided the conditions for the emergence of Middle Assyria and, later still, of Neo-Assyria, with extensive military power.

Middle Assyria

This period extends from approximately 1364 to 912 BCE. In this era, Assyria gradually became a military power and adopted a policy of territorial expansion. The greatest king of this period was Tiglath-Pileser I, whose reign dates to approximately 1114 to 1076 BCE. He carried out significant conquests in Mesopotamia and the western lands, thereby expanding Assyrian influence.

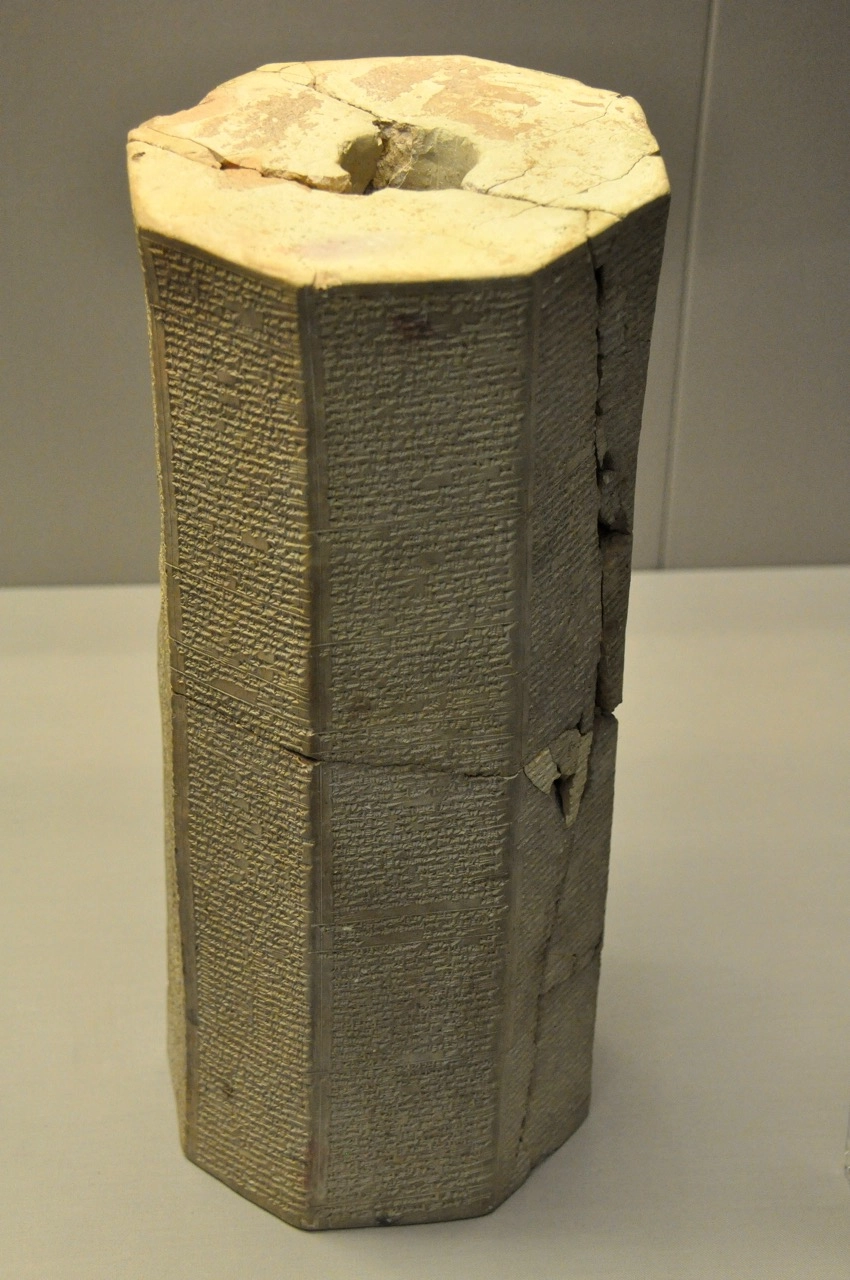

Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia

Note: the upper clay octagon records the king’s military campaigns, his hunts and construction activities in Assyria and other cities, and the restoration of the temple of Ashur.

Among the important events of the later part of this period was the emergence and gradual expansion of the Aramean peoples. In the late twelfth and eleventh centuries BCE, these peoples exerted pressure on Babylonia and Assyria. At first, the Arameans turned toward the Babylonian regions and then brought parts of the Assyrian realm into a state of insecurity. Nevertheless, these pressures did not lead to the extinction of the Assyrian state during this period; rather, they resulted in temporary weakening and the loss of some territories.

Neo-Assyria

This period lasted from 911 to 609 BCE and is regarded as the height of Assyria’s political and military power. In this era, Assyria became a great empire in Western Asia.

At this time, the Assyrians prevailed over the Arameans and brought many lands in the Levant region under their control. Despite this, the Arameans established states and cities in Syria. Damascus, Aleppo, and other important centers gradually became their political and economic hubs. There is no certainty regarding the exact date of Aramean domination over these cities, but their rise to power at the beginning of the first millennium BCE is beyond doubt. The Arameans soon came to play an important role in trade.

The Arameans adopted their writing system from the Phoenicians and devised a distinct script that later became known as the Aramaic script. This script gradually replaced cuneiform in many administrative and economic uses and spread across vast territories, including Iran, Central Asia, and other regions.

Among the great kings of this period was Ashurnasirpal II, who, through extreme violence, consolidated the Assyrian state's authority. Although Assyria at this time appeared to be the most powerful state in Western Asia, in the same period the state of Urartu—which in later religious texts was called Ararat—took shape in the northern regions and became a serious rival to Assyria. Thereafter, some territories refused to obey Assyria, and internal rebellions also contributed to the state's weakening.

During this period, Tiglath-Pileser III and then Sargon II came to power. During the reign of Sargon II, the Assyrian military organization underwent a transformation, and the national army, which had previously relied on free cultivators, gradually gave way to a force composed of mercenaries and non-national troops. This transformation, although it increased Assyria’s military power in the short term, destabilized the state's foundations in the long term.

Note: The author believes that the model adopted by the Assyrians—namely, the formation of an empire based on military power and the exploitation of subject lands and peoples—has been repeated many times throughout history. Among the more recent examples of this model, one may point to the British Empire and the United States of America. Within this framework, the dominant power, relying on military and political superiority, creates structures whose benefits are largely secured for the center of power and to the detriment of peripheral societies. In the case of the United States, examples include political interventions and regime changes, direct or indirect military interventions, the use of the dollar’s position as the dominant international currency, and the imposition of financial sanctions. Taken together, these instruments have enabled the United States to exert significant pressure on other countries and to shape the global economic and political order in its favor. The consequence of such a model, in cases such as Assyria, Britain, and the United States, has been a marked concentration of wealth and power at the imperial center and the transfer of costs to subject lands and peoples. Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that the progress of the United States cannot be explained solely by this factor, and that elements such as an effective political structure, extensive financial markets, economic innovation, and a work ethic have also played a fundamental role in this process.

Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal was one of the best-known Assyrian kings of the seventh century BCE. He is usually regarded as the last powerful ruler of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Ashurbanipal ascended the throne around 669 BCE and ruled for approximately forty-one years. During his reign, Assyria's political and military power remained intact across a vast territory, from Mesopotamia to parts of the Levant and Elam. Many historians consider this period the peak of Assyria’s military strength.

By Zunkir - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia

Note: This relief depicts Ashurbanipal in a lion-hunting scene, a ritualized representation in which the king, through direct confrontation with the forces of nature, displays his ability to establish order and authority. This pattern was not confined to Assyria and later continued in the royal propaganda of Nebuchadnezzar II and in the reliefs and stone carvings of Darius I at Persepolis. In all these examples, the principal message is not the killing of evil, but the presentation of the king as the guardian of order, law, and legitimate power—one who restrains chaos and keeps the world in balance.

Ashurbanipal was not merely a warrior king. He possessed a deep attachment to knowledge and writing. Unlike many kings of his time, he could read and write cuneiform. By his command, thousands of literary, religious, scientific, and historical tablets were collected from across Mesopotamia. These efforts led to the formation of a great library in the city of Nineveh, a library now known as the “Library of Ashurbanipal” and regarded as one of the most important sources for understanding the culture and thought of the ancient world.

Despite this cultural dimension, the reign of Ashurbanipal was not free from violence. His military campaigns, especially the wars against Elam, were accompanied by the destruction of cities and widespread slaughter. After his death, political cohesion within the Assyrian Empire rapidly weakened. For this reason, Ashurbanipal stands both as a symbol of Assyria’s cultural splendor and as the final sign of its power.

After the time of Ashurbanipal, Assyria’s prolonged wars with Elam continued, eventually leading to the extinction of the Elamite state; however, these wars also exhausted Assyria’s strength and resources. At the same time, pressure from Aryan peoples such as the Scythians and the Medes, which had begun some time earlier, intensified. The combination of these factors ultimately led to the fall of the Assyrian state. The final collapse of Assyria occurred with the capture of Nineveh in 612 B.C.E. by an alliance of the Babylonians under Nabopolassar and the Medes under Cyaxares, and thus this ancient and powerful state passed out of existence.

Srouces

Marc Van De Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East

Karen Radner, Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction

Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

Mario Liverani, The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy

Amélie Kuhrt, The Ancient Near East

Mario Liverani, Assyria: The Imperial Mission

Jean Bottéro, Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods

Gareth Brereton, Curator, Ancient Mesopotamia

Trevor Bryce, The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.

Encyclopaedia Britannica, entry Tiglath-Pileser I

Gwendolyn Leick, Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City

Encyclopaedia Britannica, entry Assyria

Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Ashurbanipal

The British Museum, Library of Ashurbanipal

Encyclopaedia Britannica, Syria

Herodotus, Histories, Book VII

John Boardman et al., The Oxford History of the Classical World